Fairmont team developing ‘game-changing’ explosive detection device

|

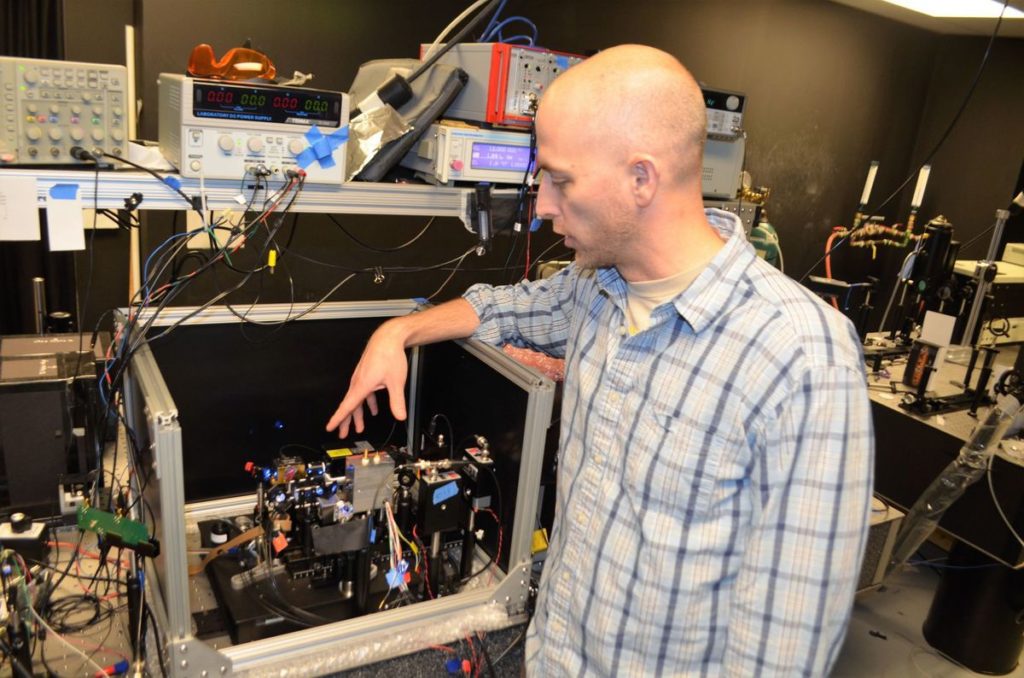

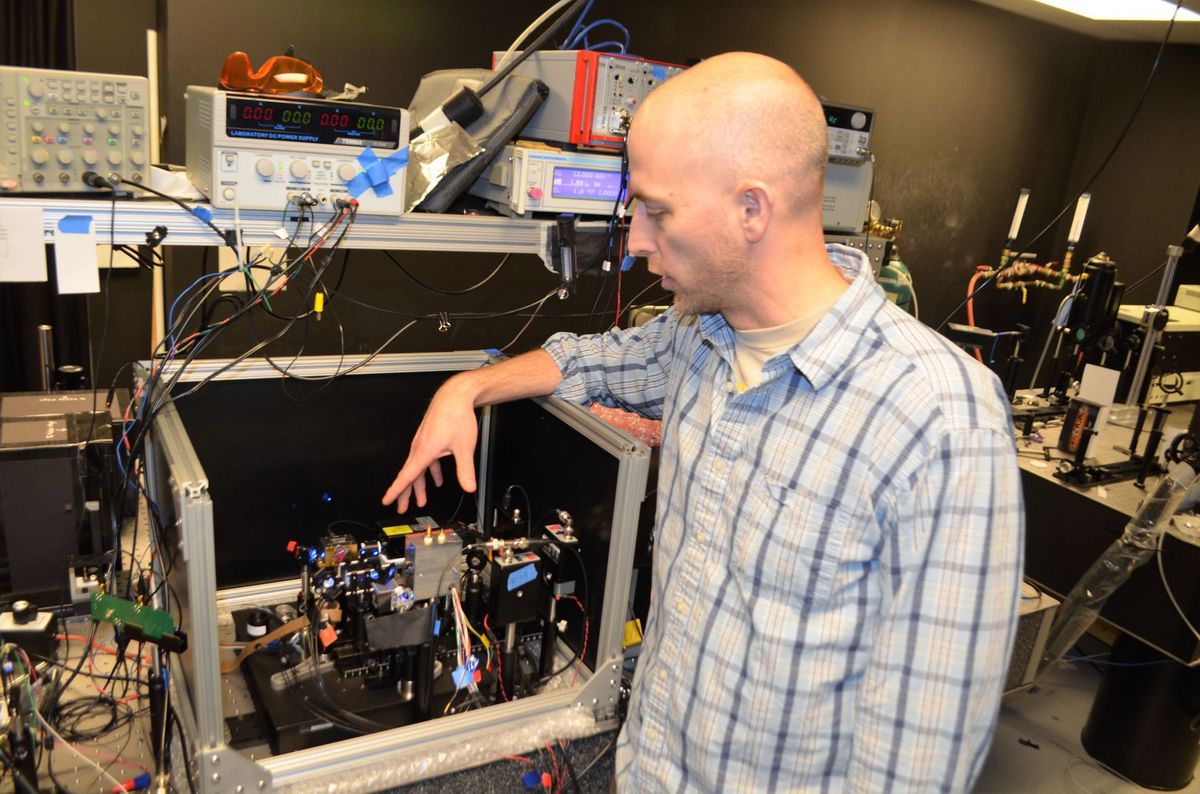

| Staff photo by John Dahlia |

| High Technology Foundation senior member research staff, Robert Martin, points to the second phase of the Deep Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Explosive Detector |

FAIRMONT — Off in the back reaches on the first floor of the sprawling Robert H. Mollohan Research Facility high atop the I-79 Technology Park in Fairmont is a small team of researchers who are quietly developing a new, game-changing technology that could potentially eliminate the threat of the Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs).

These unconventional weapons, typically hidden or buried in extremely difficult to detect areas, are responsible for thousands of injuries and deaths to coalition forces from 2001 to 2014, according to U.S. Department of Defense statistics.

The team of three, led by High Tech Foundation principal scientist Balakishore Yellampalle, have been perfecting a device that detects trace levels of explosives from a distance using something called a “deep ultraviolet laser beam.”

|

| Dr. Balakishore Yellampalle |

In this approach, Yellampalle said, a deep ultraviolet laser beam is pointed at a surface, and the scattered light is then reflected back, collected and analyzed by the sensor. A computer program then determines if the spectrum indicates the presence of explosives.

Robert Martin, senior member of the High Tech Foundation research staff, works alongside Yellampalle and software developer Ken Witt on the multi-year project. The Fairmont native and West Virginia University graduate said the real benefit of the Deep Ultra Violet Resonance Raman Explosive Detector is how it could ultimately save lives.

“If there’s a bomb down range, our system can help keep our warfighter out of harm’s way,” Martin said.

Martin is more of an electric engineer than a scientist. He works on the device itself. He explained, in simple terms what it can do.

“Trace amounts of explosives are what we want to find,” he said. “Whether it’s on a doorknob or a bomb that’s down range: Anything.”

To find those trace or potentially microscopic explosive elements, an operator would fire a laser signal from the detector to a target of interest. Almost instantly, the reflected light senses or reads materials on the target.

“Whether there’s background interference, whether there’s sand, salt or whatever it is overtop the target,” Martin said. “We want to see if there is an explosive there and then the operator can hopefully take down whatever bomb threat there might be.”

But the laser is more than just an intense beam of coherent monochromatic light. According to Martin, the system they’ve developed is smart.

“That’s called, ‘spectroscopy,’” he said. “We shoot the sample, and the spectrometer sees the light that is reflected back. So it looks at the whole spectrum of light.”

From there, he explained, the device actually detects all sorts of tiny bits of material from the laser light that is reflected back from the object. The real trick is how the system deciphers precisely what the laser is seeing.

“We shoot a bunch of stuff and build a library,” Martin said.

The library Martin is talking about is a large, intuitive computer database the team developed. The data is made up of what all types of tested items would look like, such as salt, sand, sugar, water, TNT, or even salt with TNT.

“So when we’re out in the field and we get data, whatever it might be, we can see if it matches what we’ve seen before,” he said.

The Deep Ultra Violet Resonance Raman Explosive Detector project is actually a continuation of an earlier one started in February 2012.

“We have been developing the technology in stages to meet our customer requirements,” Yellampalle said. “The current phase of the project was awarded May of 2016 for two years.”

The award phase the team is working on today is called phase three. During the second phase, the team developed a compact prototype they tested in the lab.

“Phase three of the project is getting the system down to 20 pounds or less and can be mounted on either a tripod or a bomb-bot,” Martin said.

Eventually, however, the plan is to shrink the state-of-art explosive detector down to a hand-held size, which Yellampalle said could make it more attractive to both military and civilian users.

“We are building a portable detector as opposed to other competing technologies that are heavy,” Yellampalle said.

Currently, the team at the High Tech Foundation has demonstrated the technology both in the lab and locally. The next step, as Martin said, is to take the West Virginia-grown tech on the road.

“We are at the point where we want to mobilize,” Martin said. “We want to be able to mobilize from here and demonstrate for our customer at their location.”